I wrote a few weeks ago about how Amy Whitaker’s appropriation of Hollywood’s “major dramatic question” as a personal development strategy, and wanted to touch on another thoughtful exercise in her book Art Thinking.

This conceptual framework was developed by consultant Alan Zakon at Boston Consulting Group in the 1970s as a tool to analyze a company’s product portfolio. Although the BCG matrix has drawn some criticism over the decades, and is no longer in wide use, it remains a popular business strategy concept.

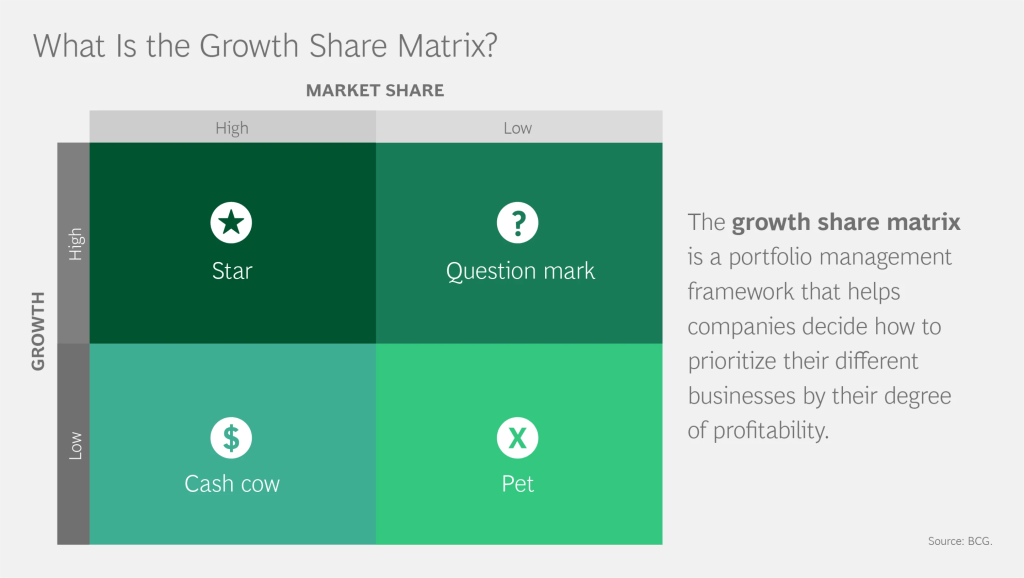

The basic premise of the BCG matrix (or growth share matrix, as it’s sometimes called) is to evaluate a company’s product portfolio against two variables: the size of the product’s market share and the market’s overall growth. The matrix is divided into four basic quadrants:

- “Cash cows” live in the quadrant of low growth and high market share. This is an investment that you can rely on to generate profits, because it is a market leader (and therefore profitable) without requiring much investment (because it’s in a low-growth, i.e. less competitive, market).

- “Question marks” are the opposite: high growth and low market share. These investments are where most products (and companies) begin: they only have a small part of a high-growth market. Question marks may not be profitable…yet. Because they are in a high-growth market, there’s opportunity for them to become “stars” if the company leverages the right strategy.

- “Stars” are high growth and high market share—there’s a lot of opportunity here. The BCG matrix recommends investing in stars. As market growth slows over time, stars become cash cows, if the company has a large share of the market.

- “Pets” are low-growth and low market share. They are usually around because of personal preference or simply inertia. The matrix recommends letting these puppies go.

The twist that Amy Whitaker offers on this structure is applying the matrix to one’s personal portfolio of investments. She doesn’t mean stocks and bonds so much as how you actually invest your time and energy.

For example, a person’s “cash cow” might be their day job; their “question mark” is their side hustle offering consulting services; their “star” is the greeting card company they run with a friend, and their “pet” is the long-running but not very popular (or lucrative) podcast.

Whitaker focuses on the money aspect of this equation, asking this hypothetical multi-hyphenate to look at these activities through the BCG matrix. How could this person better invest their time and money? Should they really build an in-home recording studio for their podcast? Would that time and money be better off invested in the greeting card company (to amplify its proven success) or in their consulting business (to determine if it’s “star” material)?

This is a powerful angle, but I’m interested in more than the money. What if we considered “enjoyment” or “satisfaction” alongside the time and money?

This opens up Whitaker’s version of the BCG matrix to consider activities like pure hobbies and pastimes, or even friends and family.

What’s the “growth potential” for a new hobby like woodworking? My blog hobby is still a question mark—what will it take to prove itself a star, worthy of my ongoing investment of time and energy? What other question marks are there in my life?

Or, even, at the big picture, what happens if my job is no longer a star but just a cash cow? Worse, what if it’s a question mark?

The matrix is a great conceptual framework because it continues to raise questions and demand refinement and clarification the more you think about it.